Originally published in The Hawk Insider’s Fall 2021 edition. Written by Christian Kabbas ’14.

On a crisp fall morning at the beginning of the school year, there was a special recruitment process taking place on RIPTA bus #3 departing Providence for Oakland Beach. Isaac Reyes ‘06 remembers it well.

On board, a handful of Bishop Hendricken students – all of them young men of color – rode the bus to school. As soon as a freshman stepped on board, they were approached by upperclassmen.

“They saw your khaki pants and your blazer and asked, ‘Are you going to Hendricken?’” recounted Reyes. “You’d say ‘Yea,’ and they’d immediately follow up: ‘Alright, we’ve got this club and we want you to come and join.’”

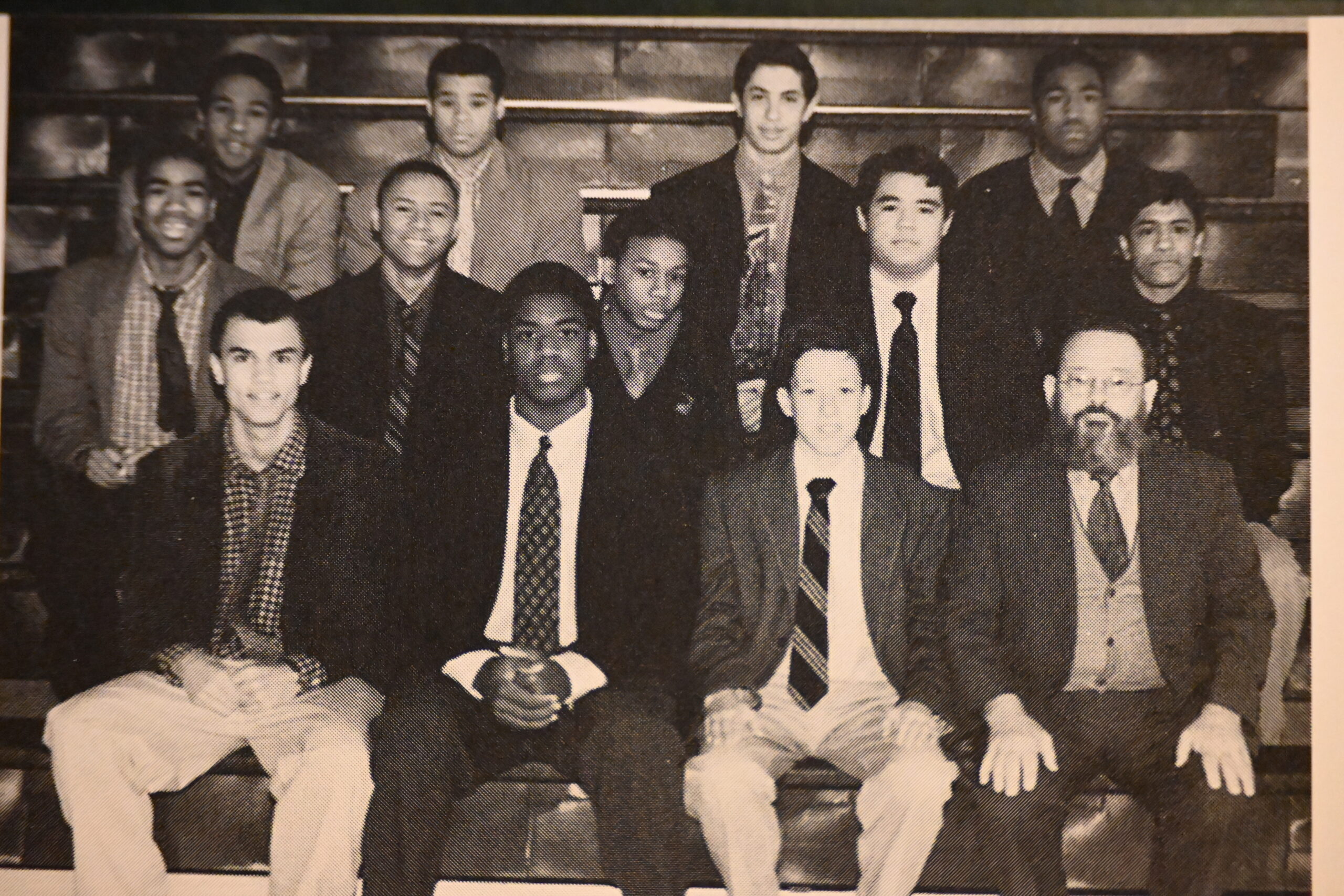

The club they were pitching was known as The Brotherhood, a group formed in 1998 to support students of color at Bishop Hendricken. Originally started by a group of students, including Curtis Coleman and Nedzer Erilus, James Poisson, a member of the Theology faculty, served as the group’s first faculty advocate. The Brotherhood grew steadily throughout the early 2000s under the tutelage of mentors such as Jack Berry and Br. Stephen Casey.

Its goal: serve as a place where Black, Asian, Hispanic and Latino young men could come together to talk about the unique experiences they shared at Hendricken.

“Most of the meetings were us talking about life,” said Joshua Xavier ‘06. “It was very informal, and I think that was the beauty of it.”

The group, which would meet regularly, became a critical home to young men who, at times, felt without one on Bishop Hendricken’s campus. At the time Xavier and Reyes were seniors, just under 6% of the student body were young men of color.

“We could discuss anything,” Reyes said. “I can remember being called a racial slur and having the members of The Brotherhood there to be my support system.”

“What we had in The Brotherhood were other individuals who were going through those unique experiences and incidences,” Xavier commented. “It was fascinating to talk about those experiences in that group because the other guys around you supported you, had your back, and gave you advice.”

But The Brotherhood was about challenging the perspectives of its members, too. In a space that was dedicated to nurturing young men who sometimes felt out of place, there was no place for one-sided thinking.

“Being 15 years old and thinking, ‘This person doesn’t like me because of the color of my skin,’ The Brotherhood was a place that challenged your thoughts,” Reyes noted. “Guys would turn and say, ‘Have you tried to build a relationship with that person?’ or ‘I don’t have issues with that teacher. Have you tried approaching the relationship this way?’”

“It wouldn’t be uncommon for guys to say, ‘Well, maybe you’re seeing the situation differently,’” Xavier mentioned. “We had disagreements.”

Like a family, The Brotherhood functioned as a group that not only looked out for one another, but also held each other to a higher standard. When members missed a meeting, others would check on them. When there were gripes with faculty members or classmates, others would offer another outlook.

“It was fascinating to see all these layers,” commented Xavier on the differing backgrounds of The Brotherhood’s members. “We weren’t just Black and Latino and Asian men. Some of us were from Providence, some of us were from Warwick. Some of us were Catholic, and some of us were Protestant.”

Within this melting pot of young men, the group found strength. And at the head of this band of brothers was Jack Berry, the group’s “biggest cheerleader,” according to Xavier.

Berry served as The Brotherhood’s moderator – and more importantly – its faculty advocate. When members of The Brotherhood were having difficulties or encountering issues, Berry was there not only to listen and challenge, but defend.

“If you wanted someone in your corner, it was him,” remarked Reyes reflecting on Berry’s impact. “You wanted to go through walls for him because you knew he would do the same for you. For many of us growing up without father figures, Jack Berry was that father figure for us; to sit there and put life in perspective, to challenge you, but also protect you.”

In addition to serving as a conduit between The Brotherhood, administration, and faculty, Berry was a mediator for all parties on subjects that were difficult to talk about – a role that was not only important to Reyes and Xavier, but critical to the group’s success.

“He was perfect at balancing all interests at play,” Xavier marveled. “He was a master at standing up for us, but also providing us the opposite perspective all while not justifying the mistakes. I don’t know how he did it.”

“Provide and preside,” Reyes added. “That what a father would do.”

While The Brotherhood was an important mental health resource and social support to its members, not everyone understood its role for students of color. Reyes recounted some of the misunderstandings from his classmates: “Some thought we went there and talked about gang stories in Providence, or shootouts on our streets. But it wasn’t that. It was something that we needed.”

The Brotherhood forged on until it slowly petered out in the mid-2010s. Following a roundtable discussion on diversity, equity, and inclusion at Bishop Hendricken in the wake of the George Floyd murder, Xavier recommended that if students felt they wanted to have a group like The Brotherhood – to talk about their unique experiences as young men of color – they should.

In spring 2020, after engaging students, Bishop Hendricken launched Born to Stand Out, a group for students of color inspired by The Brotherhood. Today, the group has Xavier’s and Reyes’ classmate, John Manning ‘06, as its faculty advocate alongside Sarah Murray, Dean of Teaching and Learning.